Globe and Mail, January 26, 2016

Globe and Mail, January 26, 2016

by Thomas Homer-Dixon

We’ve been lucky so far, because the bad guys have usually been stupid. But they probably won’t be stupid forever, so our luck probably won’t last. When it finally runs out, we need to make sure we don’t do the bad guys’ work for them.

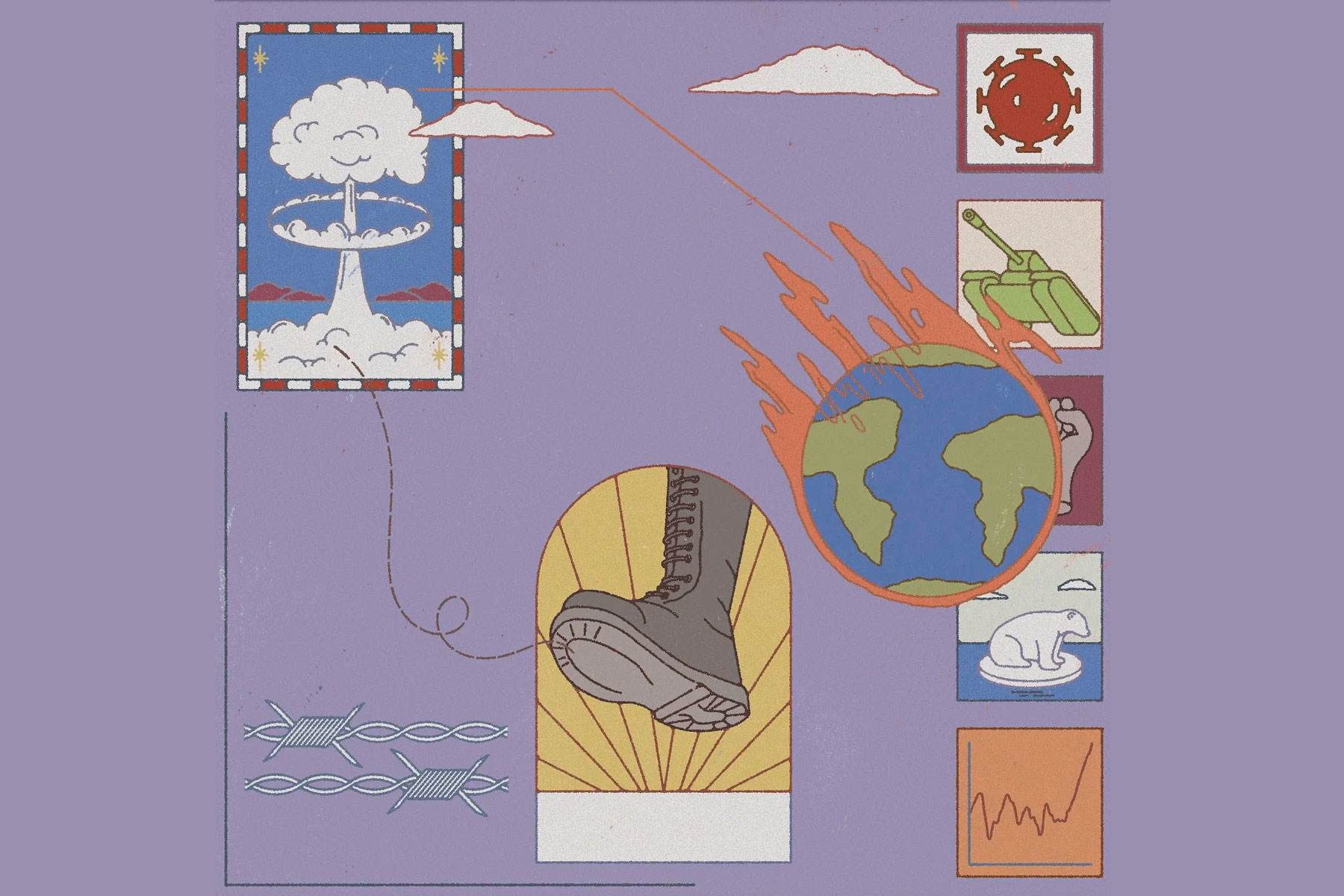

Around the world, violent political extremists, including terrorists, are using the technological and social products of the Enlightenment to try to destroy the Enlightenment project itself. They co-ordinate themselves using smartphones and encryption software, arrange transfers of money through the Internet, recruit new members using social media, and kill people with modern assault rifles and high explosives. They exploit liberal societies’ protections of privacy and of freedom of movement and association, and they attack soft targets where unarmed citizens of our open societies congregate.

It might seem that the people doing these things are all Islamist radicals because assaults originating with the Islamic State in Paris, Jakarta and San Bernardino are in the headlines. But in the United States since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, far-right extremists have killed more people than violent jihadis.

And don’t forget the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo and its deadly sarin attacks on the Tokyo subway in 1995; or Norway’s Anders Breivik, the right-wing fanatic who killed 77 young people, in a lone-wolf attack in 2011. The common factor across all these wingnuts isn’t Islam; it’s an antipathy toward liberal society and an effort to exploit the most powerful means available to destroy that society.

The Enlightenment gave us modern science and technology; an emphasis on the use of reason and evidence in human affairs; a commitment to the free flow of ideas among empowered and open-minded citizens; and a powerful sense of optimism that people and societies can improve their lot. Assault rifles and high explosives are – somewhat paradoxically – the products of Enlightenment science, as are smartphones and social media. Modern science often operates through, and is invigorated by, a free market of ideas and commerce.

The Enlightenment project generates constant change, novelty, and creative destruction. Few anchors exist in this churning world, other than commitments to tolerance, reason, and limits on arbitrary authority. But it’s exactly these commitments that are anathema to today’s violent extremists. They hate change, except perhaps backward to some imagined utopian past, they thrive on close-mindedness, and they prize blind deference to authority.

In recent years in the West, a bizarre alliance of left wingers who link science to corporate exploitation and right wingers who deny climate change and the reality of our environmental crisis has laid siege to our commitment to scientific reasoning. In countless subtle ways, this assault has weakened the foundations of our larger Enlightenment project. It has helped to lay the groundwork for support for the authoritarian populism of Marine Le Pen and Donald Trump in the wake of recent Islamist attacks. When our core philosophy of tolerance and reason is belittled by many of the people it benefits and empowers – when it becomes just one creed among many with no special status – we can jettison it more easily when we’re afraid.

Violent political extremists are leveraging this malaise. So far, the number of deaths they have inflicted hasn’t been large compared with, for example, the carnage we unthinkingly accept on our highways. But every mass attack brings us closer to panic and the free decision to ditch our extraordinary freedoms. “If there’s one more 9/11,” writes New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, “many voters will be ready to throw out all civil liberties.”

Alas, time and technology are on the extremists’ side. If not carefully monitored and controlled by the state, our societies’ flow of ideas and technologies gives extremists ever-greater power to organize themselves, identify our weaknesses, and kill people. And by increasingly concentrating people and wealth in densely connected urban hubs, we’re giving them tempting, high-value targets. Explode a radiological dirty bomb in the lobby of one of the new megatowers in New York, and you’ll change the course of history.

The advantage lies with the offence. Extremists only have to succeed occasionally to achieve their ends, and the cost of any single attack is relatively low. Our open societies, on the other hand, have to succeed in stopping attacks all the time, and the costs of constant intelligence and surveillance are immense.

So far, extremists haven’t been smart: They haven’t yet effectively exploited available technologies or our open societies’ vulnerabilities. They’ve used assault rifles in theatres, not dirty bombs in skyscrapers. But eventually one or more of them will be really smart. When that happens, we mustn’t let our fear destroy the freedoms that extremists hate most.

Top Photo: CloCkWeRX (CC BY NC SA 3.0)